This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Take two of my projects 30 years apart, one recent work and one early scheme; despite the lapse in time and their very different contexts, they reveal much in common.

Ancient sites – earthworks – reveal ruins, medieval or Palaeolithic remains. We, the architects, always begin by disrupting the ground, sometimes very violently. Some primitive cultures, such as the Incas of the Andes, for whom Pachamama – Mother Earth – is a divinity, have a special ritual allowing the builders to ingratiate themselves with her before starting construction, before digging the foundations.

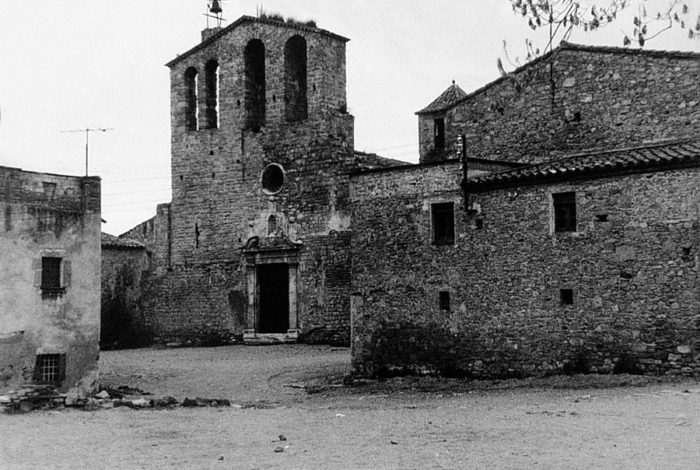

When I was approached in the early 1980s to work on the urban design of Ullastret, in northern Catalonia, near Girona – a place of great archaeological and historic significance – it was a rural medieval village. It was not urbanised. Bare earth still formed the surface of public spaces, and the infrastructures (water, light, sewerage) were chaotic and rather precarious. My role was to ‘urbanize’ the village. In Ullastret, in the country, where we had to pave the public space, we first had to regularise the random, irregular topography. This rationalised reconstruction of the hillside’s geometry in relation to the movements of people and rainwater flowing over its surface was fundamental. This operation was, for me, magical. As an inhabitant of a city from which the earth on which it stands disappeared from sight long ago, I wanted to undertake this operation of necessary modernisation with a subtle, special, sensitive approach to the place and its voices. What interested me was true modernisation that also appreciated that complex of remains: of Roman, medieval and present-day fragments, which, with almost childlike interest, I gazed at in amazement.

The Filmoteca, the new headquarters for the Film Theatre of Catalonia, was to be built in the Raval district, one of the oldest parts of Barcelona’s historic city. Here, it was not so much the earth that attracted me at first (later my relation with it prompted long, complex processes). What initially interested me was the socio-morphological content of the place: the old Chinese Quarter; abject prostitution and constant wretchedness for centuries. It has also been the site of frequent fighting, of violent scenes from even the recent past. The plaza is named after Salvador Seguí, an anarchist who was killed there, for example.

This dark, suffocating world, the subject of film, photography and thrillers, was the area where I was to intervene; thereby changing, modernising. As in the case of Ullastret, I wanted this change to be special, sensitive and in keeping with the telluric force of that which already existed. I did not want my passage through this place to be bland, mannered or standard, incapable of responding with the necessary energy; an unworthy antagonist.

The dense city context of the Filmoteca meant that when construction work started it revealed foundations, old walls, settlements. Here, the objective was not to construct a surface as in Ullastret, but to build upwards, to generate a volume. A volume that would comprise walls, planes. The logic of the wall and its direct constructive expression, with the nails, the iron bars inside it, are a fundamental part of its character. It was a matter, then, simply of adding one wall more to its ancient, dilapidated neighbours. In the old town of Barcelona, my building sets out to express itself as pure structure – no cladding, no finishes. The bare concrete beams-cum-walls that form the facades are very varied, proving themselves members of the family of the dilapidated neighbouring walls, where plaster crumbles to reveal their original central mass.

In Ullastret, the surface of the newly geometric site had to be clad, its skin defined. Here, the idea – I would almost say the delirium – was for this horizontal cladding to react always to its direct environs, to the walls of the facades: with no boundaries and with no other internal logic than the one provided by the geometry of the topography beneath it. The fragment was the rule. Ultimately, each square centimetre was a specific problem. A system cannot last very long in a medieval city, and working with pavement meant obeying the general urban logic, in this case fragmented and multiple.

The Filmoteca is volume, not surface. It has inner space. Light is the protagonist. Light constructs movement, accompanies movement. The space is organised around two movements. The first is a descent into the darkness of the cinemas, with the reflection of the spectators (in turn reflected; actors seen in a series of mirrors). The second movement is an ascent towards the light, towards the places of work. Returning to the above-grade volume, and in contrast to the lower space, the ascent from the foyer to the upper floors of the building is accompanied by natural light, introduced via the great skylight above the courtyard where the escalators are located. Two courtyards, connected but not continuous, accompany and orchestrate the movement.

In Barcelona’s built-up old town, it is necessary to control the relationship with the exterior world. The basalt stone covering Plaça de Salvador Seguí, arranged in the style of Portuguese pavements, makes its way into the foyer of the film theatre, connecting exterior with interior. The spacious foyer is lit via panoramic openings that frame the immediate urban landscape, like CinemaScope screens. The cinematographic metaphors are not just conceptual; they are above all physical, sensible. In the old town, with the very close proximity between buildings, interaction must be mediated; filtered. And this is implemented by a variety of devices with vague cinematographic references. Juxtaposed on the walls, a system of filters, all different, in keeping with specific uses, protects the interior and opens it up, carefully, to the outside. Its relationship with the exterior is sieved by a series of patterns made of wire and perforated metal sheet that filter daylight and give the occupants privacy, allowing them to look out without being seen. Inside, the use of filters continues on the upper floors. Coloured glass screens divide the space and, like the filters and diaphragms used in film cameras, control the intensity and the colour of natural light. The filter is a mechanism used by film; the content of this building.

But beneath this all, in Ullastret and in Barcelona, it is the ruins that unite them: Roman remnants that formalise the planes of foundations and drains, and mark out the new structure of the buildings that follow. In time, walls are destroyed and roofs disappear. It is only that which lies below the surface of the things that remains: those ancient earthworks, from which new worlds are planned.

Josep Lluís Mateo

Barcelona, aeroplane to Lima, April 2012

Earthworks, MATEO, Josep Lluís, Architectural Design, Human Experience and Place: Sustaining Identity, profile nº 220, Text © 2012 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Photos © 1985 Jordi Bernadó, 2012 Adrià Goula Photo, 2007 mateoarquitectura.